THE INTERVIEW

Ela Wasney

1. Could you share a bit about your background and what led you to start your art practice?

I grew up around Garson, Manitoba, on a beautiful rural property, to a very creative mother who nurtured those same instincts in myself.

I can't really remember a time when I wasn't drawn to visual arts. I did all my schooling in Selkirk, a smaller town, but I made sure to be involved in any of the creative classes or events they offered throughout my primary education. When I graduated high school, I initially tried to be a bit more practical about my future. I come from a working-class family—my father's in the trades, my mother's a nurse—so I pursued a Bachelor of Science at the University of Winnipeg. I did a year of lectures there and didn't see a fulfilling future for myself; I was missing something.

So I took an art history course, and it felt better, but I was still lacking that hands-on tactile approach I'm more drawn to. I took a leap by applying to the School of Art at the University of Manitoba and finished their four-year studio degree. Since graduating, I've been trying to find my place in the arts.

Q: Were you making art before then?

Yes, but not in the sense that I am now. It was purely an attraction to visuals and beauty and colour and all these things—but never really putting it all together.

I think it was more so in my last year at the School of Art, when the work was self-directed, that I found an understanding of art-making and started thinking more about what I want to say and how to share it.

2. What themes does your work explore?

I think it explores rural culture as a whole, which includes stereotypes, class, religion, and beauty and pastoral aesthetics.

I explored religion more heavily in my practice during my honours year. I’ve moved a little bit away from that, but there’s still a veil of religion, I feel, that encompasses rural communities—so it's something that's on my mind, but not as prominent as it once was.

My work definitely reflects my personal upbringing, and I want to bring those ideas into the arts community and share them with the public eye.

3. How has your work evolved over the years and what has influenced those changes?

I think it's become more direct—now having time to really sit with an idea rather than making something to fulfill a project or a strict set of guidelines, and being able to really meditate on what I want to say.

A formative experience for me was my graduation show, where my extended family came to a formal gallery space—somewhere they really wouldn't normally engage. They came to support a family member of theirs, but my impression was that they left happy to see a reflection of themselves in an art space.

I think that's really missing, and something that I'm trying to help mediate—giving space to people who don't engage in the arts, arts activities, or cultural endeavours, and being able to create an approachable environment for them.

Q: Do you think it was obvious to them when they entered the space that this was reflecting their identity?

I think specifically for my family members, yes—because I used images that they would be familiar with, like archival family things, but also, just that they understood it. It wasn't an abstract idea that they really had to work toward or something that made them feel lost or uncomfortable because they didn't understand what was going on.

They could see it. My work may be a little bit more on the nose, a bit easier for them to take that first step and be like, ‘Okay, it's beautiful. I get it. I see myself and I enjoy it.’

Even if it's just a basic emotional response and not something that they really have to labour over.

4. What is the biggest source of inspiration for your work?

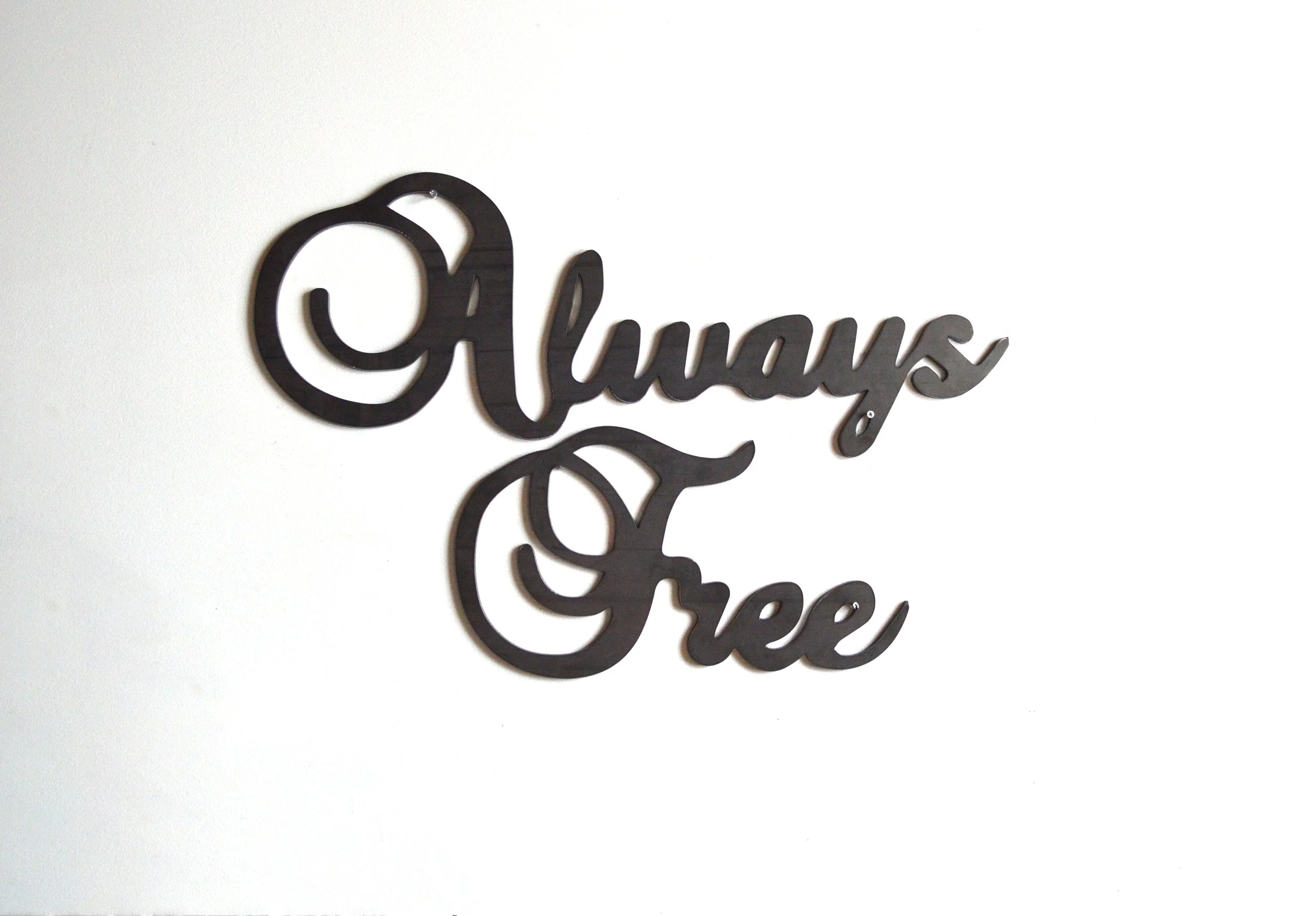

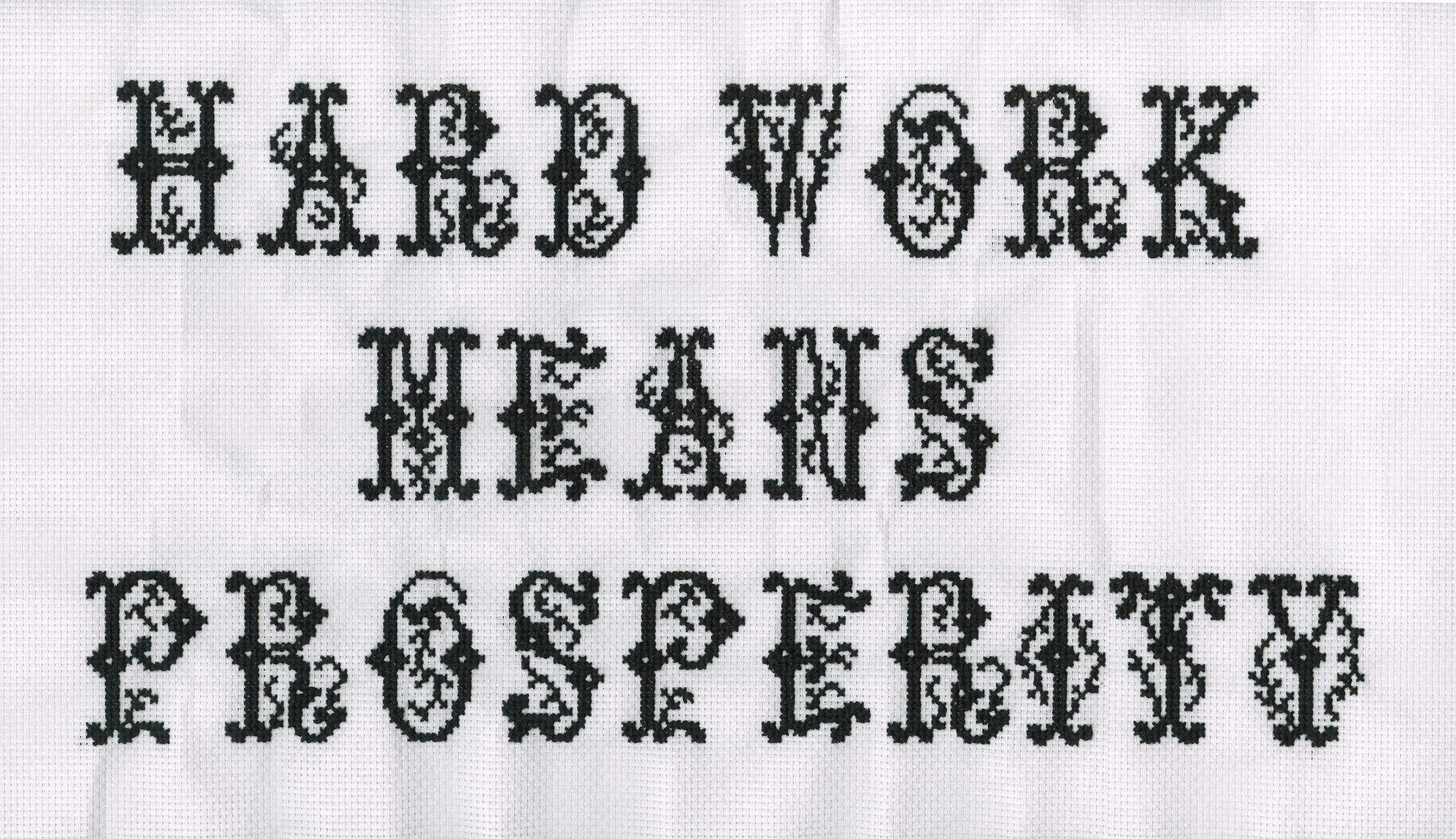

Something that underlies most of my work is roadside advertising signage.

A lot of my work is text-based, so I use these found texts as a jumping-off point for a lot of my pieces, and I return to them quite often. They could be handmade signs that people paint and stick up at the edge of their driveway, or decals on cars—any vehicle that people use to spread or express their personal beliefs to the public.

I think this phenomenon also reflects a similar feeling of being unheard or perhaps alienated, as discussed earlier. When people go to lengths to build something by hand just to get it out into the world—even if it's something that’s a little more DIY.

5. What is the most challenging stage of the creative process for you and why?

In my practice specifically, I think it's figuring out what to do with text once I find something that really resonates with me.

I love exploring materials, so working with steel recently was really exciting and interesting—something I hope to explore more. But I think just finding a way to manipulate the texts so it feels more tangible or present is a common struggle. Text is ephemeral; I want to do something with the ideas or phrases I come across—but it's about figuring out what to do with them and how they'll be most effective.

Q: The pieces of text in your work, are they all taken from real signs or stickers you've seen on the road?

A resource I return to often is an Instagram account—@back_of_a_truck. They get submissions from all over, mostly North America from what I gather. People will be behind a truck, car, or trailer that has a really crazy custom-made decal and send in pictures of them. You can't buy these decals in stores, so it makes me think a lot about the drive to create them. You have to know what you want to say, figure out the font and the size, get it made somewhere, and then install it. It's a pretty intense process for something that's so simple and technically unnecessary.

So not all of the text or images are wholly mine; some are things that I've seen in real life or came across elsewhere. Some of it's just scraped from the internet in one way or another, then reused and manipulated in other ways.

Q: Have you always been drawn to that kind of imagery, or did discovering the Instagram account spark that interest?

It’s something I have seen throughout my life, so the imagery is familiar. It’s nice to have that variety in one place, but it is something you can still see just taking a drive outside of the city centre. Everybody has something to say; sometimes you just need to look a little harder to see it.

6. What is the project you're most proud of to date?

I think my pew, John 6:10.

It is one of the most involved pieces I’ve created. From the physical creation of the work to the responses to the text itself—I learned a lot from it. The text held a sense of duality. To me, it felt almost threatening. But at my grad show, I had a family approach me whom I knew was quite religious, and they loved it.

It is also one of my only interactive works. The CNC-carved text acts as an embosser when viewers sit upon it. However you feel about the message, it physically stays with you for moments afterward.

7. Do you see yourself staying in Winnipeg long term, or are there other cities that inspire you to work there?

My long-term goal is to return to the countryside and not live in any city.

What Winnipeg has given me in community and opportunity, it has taken in energy and space. I know it's a much slower city than, say, Toronto or Montreal, where there's always something going on, but it still feels quite fast-paced for my liking. I really want room all for myself. I don't think another city would do it for me.

It's tough, because in my adult life and contemporary practice I haven’t had that kind of space, so I'm not sure whether it would be detrimental or maybe amazing to have that physical room to explore. I might be romanticizing it a bit, because I've been away for so long and I know it's different.

8. Do you think your practice would look different if you were based in another city?

I think so. My practice is very much rooted in personal experience, and that’s a result of environment.

9. What would you like to accomplish in the next few years?

I just want to prioritize creating, exploring, building my portfolio, and simplifying my direction.

I feel like a lot of my current work explores related but broad topics. Being able to bring it all together would be helpful, and I think that comes from a lot of reading. I’ve found a lot of great non-fiction books that I have been slowly moving through. Most of the content I’ve accumulated relates to politics and class systems, and I believe this research will inform my practice for years to come.

10. If there's one thing you hope people take away from your work, what would it be?

I think just a sense of understanding. What I really want in the end is for people like my family—my community—to come out and enjoy art, to see themselves in spaces where they can find some sort of creativity in themselves.