THE INTERVIEW

Caroline Mousseau

1. Could you share a bit about your background and what led you to start your art practice?

Art has always been a part of my life in some way. Both my grandmothers are painters and always have been. My mom always carried folded pieces of scrap paper and a bunch of pens and pencils in her purse for me, so I could draw everywhere.

I have vivid memories of sitting in restaurant booths where the table would reach my chin and my elbows would be at my ear level while I drew over and over again; or drawing on loose papers at picnic tables, or on the seats of metal bleachers outside.

It was just a constant for me. It was very much my own world, my own time. But the sounds of things happening around me always infused the experience with a unique ambience that became a part of that repetition. I was always listening at the same time, like by osmosis— through a permeable layer.

It's funny to think that my process in the studio now isn't all that different in terms of how much time I spend surrounded by echoes of colour, with my current work, and sound; I always need some noise going on. That repetition keeps playing a strong part in making my work and in thinking about painting in general.

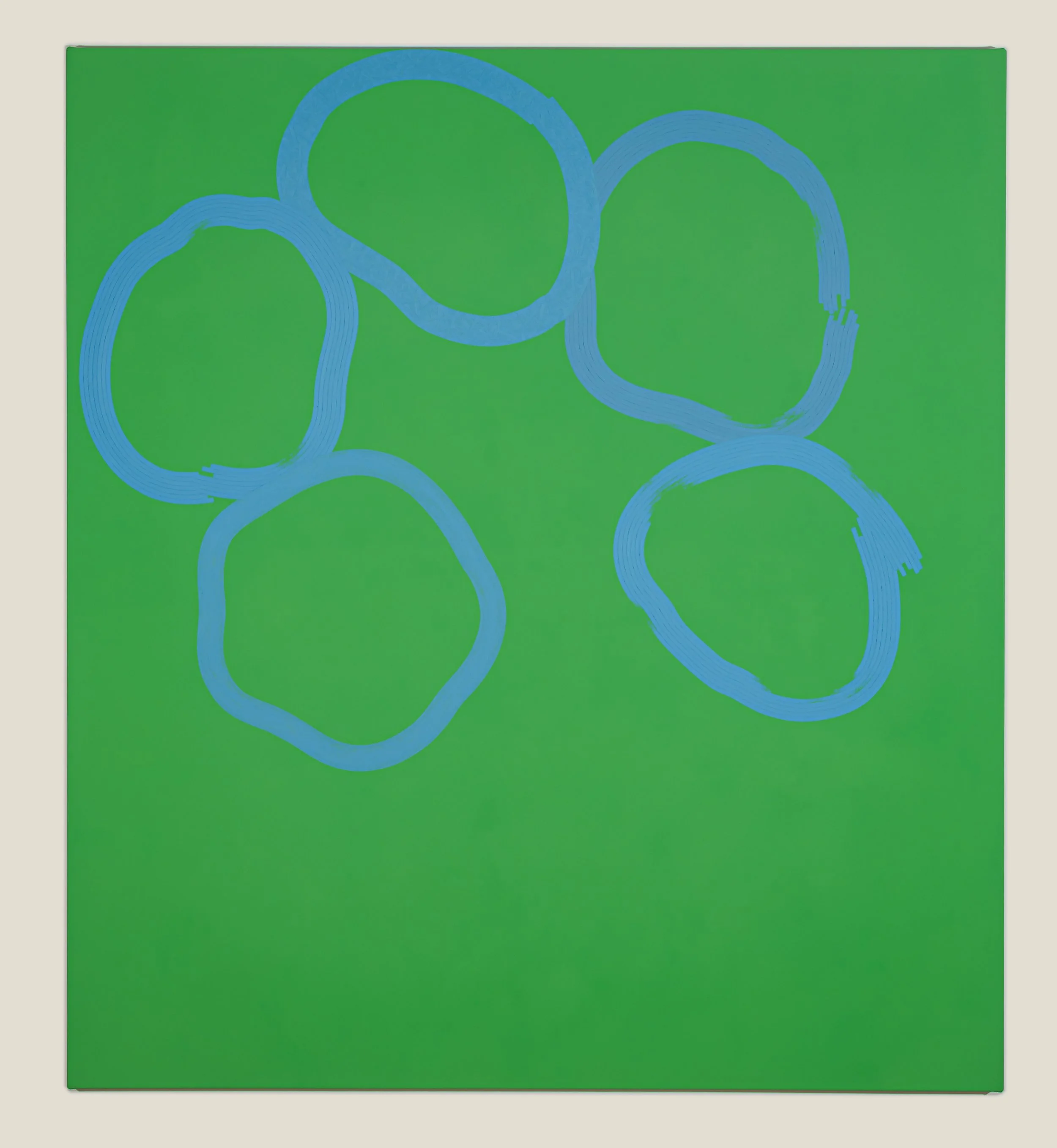

One of my grandmothers in particular paints constantly. She makes these nonstop patterns of abstract flowers and roses in pinks, purples, and greens, and they fill every possible surface. They're almost modular. Each one is just four or five strokes of paint that curl into each other. The colour and the vibration of that pattern is the first thing that comes to mind when I think of her home; she made a space for herself—in a physical manner, but also in an emotional one.

The more I work, the more I realize just how important her gestures have been throughout the last ten-plus years of my practice. She has never really considered herself to be what we call a Painter with a capital P, but there's a nice blur between art and craft there. It absolutely found a way into my understanding of painting much earlier than any chance to look at paintings in a gallery or museum, or any formal education.

I have some of her little magnet paintings in the studio, and I still think about her gestures a lot. They loop through my work in a sideways fashion. I think there's a spirited belief and a language there that I find important, and a strong person-to-person contact that I always want to find or recognize in some way in my work.

2. What themes does your work explore?

I've been working with abstraction and painting since my early twenties in different ways, but the main pull that keeps emerging is attentiveness. A kind of attentiveness that allows us to feel

ambiguities, even when they're difficult to pinpoint or explain. In the last several years I've been exploring the way slowness and repeated effort draw attention to abstraction as a shifting container for perception, and time.

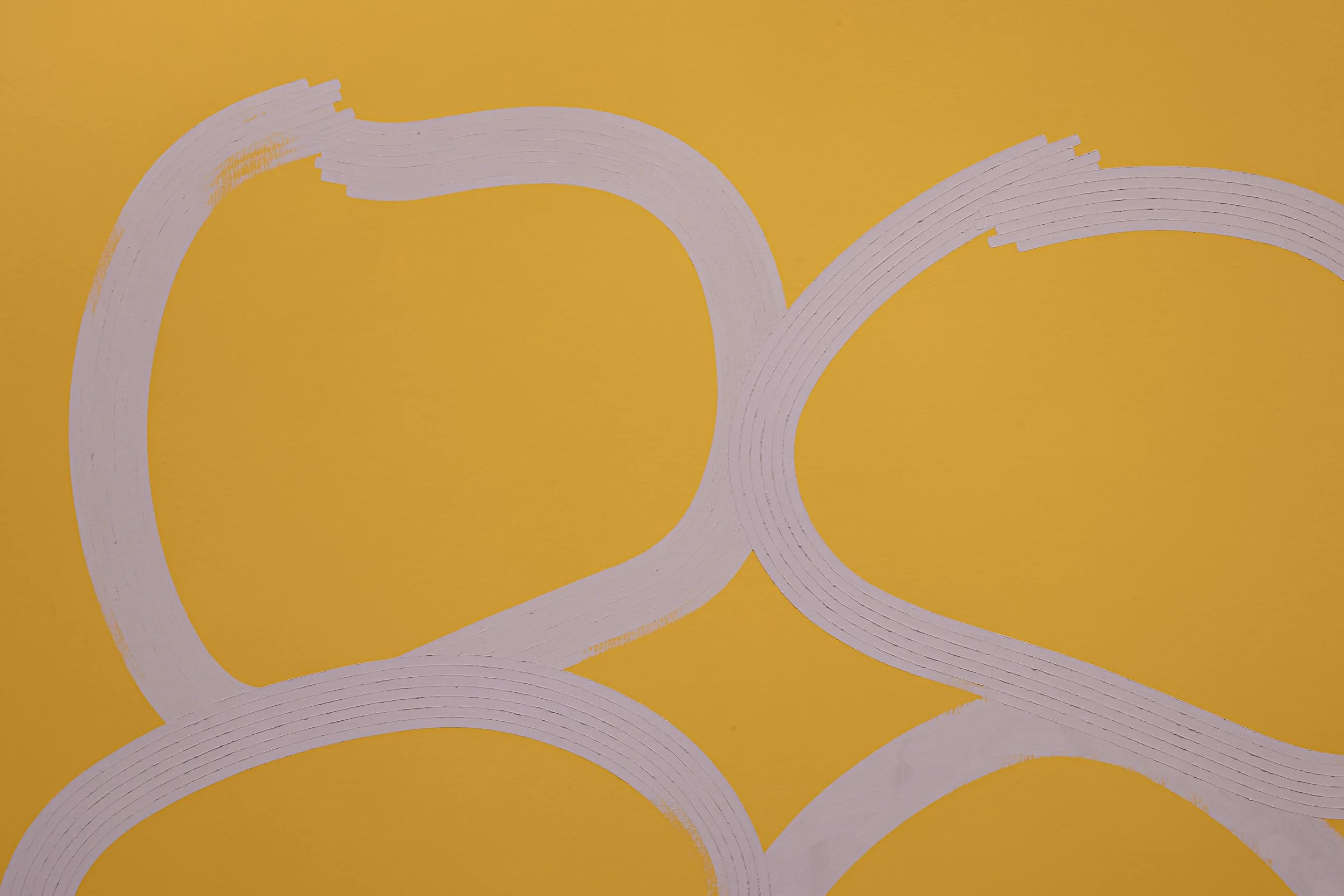

My process is really driven by painting’s material; how material and abstraction can offer temporary openings for us to experience many different points of perception—often in a simultaneous fashion. I often use accumulation to do this, building up layers of material and colour, or repeating small, labour-intensive marks into these wider gestures.

I use materiality to complicate the act of observation itself—so slowing, or stuttering perception through changes in physical or optical depth.

Painting is a spatial and a temporal practice for me. I look to abstraction to draw on the gendered charges that persist from historical separations of certain formal elements. We can think of ground from figure, whole from detail, center from periphery, mind from body, art from craft, et cetera, et cetera. The list is long, so there are many implications to gesture.

My process has become one of responsive orientation through all these ongoing legacies, but especially immediate gesture and devaluations of the mark or mark-making. There’s a fluctuation there, and I use formal components of abstraction to open some ambiguity and anachronism in my work.

I find that it becomes a productive space of friction, and detail is important in this because it can stretch, it can puzzle, it can even remove the possibility of reading a painting immediately. So I work with fleeting detail, or perplexing detail, a lot to invite embodied ways of looking with viewers.

For me, it's crucial to think about the surface because there are so many silos and presets that we face every day. I'm interested in how surface can encourage movement and connection instead of closure. Abstraction has that potential because it challenges extreme specificity in interpretation—it can really linger. I find that quite useful.

3. How has your work evolved over the years and what has influenced those changes?

I have long-term relationships with certain aspects of my work, since I find there's so much potential in the detail and nuance of repetition. There’s a consistent undercurrent so it might seem like the work doesn’t change much, but it has evolved significantly. You can see change in every single mark, even when they're drawing a parallel right to the side of another one. They follow similar paths but are completely different. It's the minutiae that's captivating.

I started with patterns and sequences in one way or another quite early when I became interested in abstraction. I always loved Agnes Martin—the way her grids in paintings and pencil

drawings show us a great sensitivity through repetition. For me, repetition is a way to constantly reach for, or move towards, something. Each detail or action is a small transformation, or an attempt to orient yourself in relation to something or someone else while holding on to difference. That effort in reaching is what’s important—and has changed a lot in my work over the years.

I think my process of accumulating detail together has an affinity with what Sianne Ngai calls ‘thick language’. It's a kind of thickness, or an opacity, or a stupor that resists the idea that we can ever communicate quickly, or definitively, or categorically. There's often a quick first impression of my work—when the colour and simple forms really take the lead—but as time evolves with it, there are all these subtle interplays and visual contradictions in texture, direction, movement, and shifting light.

I can often see people try to perform the painting in their own way as they bend to follow certain strokes, or over stretch to find little gaps that are here and there. They try to mimic those gestural directions. There's a lot of reciprocal movement between the compositions and people in a space, as if trying to reach for what the other is saying.

The relationship develops from all sides and that is most present in my recent work.

Q: Do mark-making and repetition connect to the idea of osmosis you mentioned earlier, and to more unconscious ways of knowing?

Yes, in some ways.

As a painter working in the studio, I'm quite insular. I spend long stretches of time in there, with ideas that gradually take shape one mark at a time. So, there is a responsiveness or exchange that grows with that repetition. I also build colour in layers so they can radiate or move through the edges of their shapes. But I can’t fully know what will become of it all in advance. I look for movement between elements more than a settled balance.

4. What is the biggest source of inspiration for your work?

It has to be colour. Anywhere, in any form.

Q: Do you find it harder to come by that colour in the Prairies?

No, actually. You're always reminded of how colour can shift with a huge range of speed and degree.

We can think of painters like Agnes Martin again, and Wanda Koop—there's some commonality in their use of colour. In the prairies, the sky is almost like this giant projection screen where colour glows and detail is so intertwined. The scale of colour is very present. On one hand, you have massive colour, and then on the other, you also have these tiny, minute details that you have to pay attention to. They’re easily overlooked if you don't.

I think that’s an important dynamic in my work—shape can only hold on to colour for these brief, fleeting moments. I’m very interested in how precise uses of colour can serve to embody those moments of disorientation—to highlight how a perspective is never fixed.

I look at the work of a lot of painters who are strong colourists. It’s a huge list, but artists like Harriet Korman, Tomma Abts, Stanley Whitney—whose work I just saw in Minneapolis last year, which was phenomenal—Suzan Frecon, Beth Letain, Karin Davie, Ellsworth Kelly, Joan Mitchell, Mary Heilmann. It can just keep going, but I don't keep many images in the studio. I prefer to have hints of those artists and their colour relationships in another space, in the back of my mind—more like loose memories that become something else over time.

A few years ago, I came across theorist Elizabeth Freeman's idea of ‘temporal drag,’ which is a kind of formalism that plays with the familiarity of forms that can trail behind a current moment. And it also calls on all those different connections with the word—so from delay to performance, et cetera. I find the idea exciting because it connects queer and feminist concerns through a longing or pleasure for forms that are untimely or outdated, and that pull of the past becomes a call for deep attention to our present state.

At the time, I was in the middle of making work for my show, That Nagging Feeling, and I was using colour to reach for equity between the figure and ground—to flatten the hierarchy between them. Each component in the painting had a different hue, but they reached for the same value, meaning the elements in the painting had the same implied gray. Because of that, the paintings had a real buzzing opticality, to the point that afterimages would appear and the figure itself would slip out of the frame to follow and linger in your field of vision.

Freeman's idea was a turning point then, and I keep returning to it today in different ways.

5. What is the most challenging stage of the creative process for you and why?

I think for many painters it's deciding on when or where to finish a painting that can often be the most challenging.

But for me, it's the opposite—it's the start. I get enthralled with colour and its endless possibilities, to the point that I can lose myself in that pleasure and play for quite some time without it taking any form at all.

I'll just have these piles of oil paint on a few palettes on the floor, with a large number of colour swatches and samples around, to get a sense of what type of relationship—or almost circumstance—presents itself, and what shape or composition I might find or form from it.

There's an extended form of labour in the mixing process itself. You lean colours one way, then another, then again and again. They all shift in strange and unexpected ways. It extends and transforms over time to eventually jitter on the canvas or paper.

There is a form to colour in my studio, as literal masses of paint, but then there’s also a yet-to- be formed idea of shape or composition in the work itself. I often look for shapes that have a feeling of being mutable, or difficult to describe as a shape, so it does make starting a painting difficult. They avoid being fully contained in one way or another. There's this tension with the shapes having defined outlines and crisp edges, while also escaping that descriptive language. Colour has a big role in that dynamic, in how a composition can eventually push back with its own ideas. Colour and form are fully entwined for me.

Once I find a bit of footing with colour, then I can slowly gather momentum. I often describe my process in the studio as an old locomotive. Difficult to move at the start, but it gathers rhythm over time and for long stretches.

There's a weight to painting that I have to let go before getting to the studio, so that I can find my own points of gravity in the work. You see that in the shapes as well. They all droop, or bend, or lean a bit, and have different gravitational points.

So, I walk a lot. I walk to the studio and in my day-to-day. It's not a casual walk. It has a pretty high cadence, but it's not a jog either. I think it mimics the way I work, and how the paintings can show up when you see them. They're quick and zany at the start, with colour popping at first, and then unfold in their tedious mark-making. They're almost a bit too fast, or too slow, for what should be happening.

6. What is the project you're most proud of to date?

I'd have to say the work in my solo exhibition, Wrestling with Static, at aceartinc., which is an artist-run centre in Winnipeg.

It came out of such a strange, blurred time with so many signals at once, like that constant gray noise from old TV static. It was the first complete body of work I made in Winnipeg and presented to the community here.

I think a lot of my work is like a constant or conscientious tinkering. For example, how colour and detail play in one painting and through a body of work as a whole. So, eventually, that tinkering develops really tactile works with constant refresh-rates of colour. Wrestling with Static showed a new and intimate version of that approach with the small, framed works made of oil and oil pastel on paper. They were mostly drawn in layers and also had some collage elements.

My recent exhibitions have engaged viewers very closely while they move in a physical space, but in different ways. Wrestling with Static had a real shift in material and to an intimate scale. I'm always interested in colour and painting's ability to morph with its context over time and disorienting the idea of direct linear histories. The more I worked with the formal elements of painting and drawing in Wrestling with Static, the more difficult it becomes to fully understand them as one or the other.

In some ways, it feels like I approach painting more like drawing. Their gestures are often coming from the repetition of line, and then my drawings are a bit more like paintings, because the paper works are often driven by shape. There's a lot of freedom in mingling those different types of presence.

Q: Is establishing a physical connection with the viewer important to your creative process?

Yes, absolutely. It goes back to that attentiveness—the work will only give as much as you offer back. So, there's a very personal relationship in that exchange.

It becomes a unique form of communication, and it's bodily.

I often think about this through the lens of craft, and it connects back to my grandma as well—repetition as the sharing of units, where they can become a language that repeats and repeats, and is interpreted in different ways, by different people, but creates a connection between them. That has been such a strength of craft.

7. Do you see yourself staying in Winnipeg long term, or are there other cities that inspire you to work there?

I was born and I grew up in Winnipeg, as part of the French-Canadian community here, so my experience of the city is split into different parts.

In the late 2000s, I went to Vancouver for ten years but I always came back to Winnipeg at least once or twice a year.

After that, I went to Guelph for my master's degree from 2018 to about six months into the COVID pandemic. I finished my graduate studies in mid-2020, so I decided to move back to Winnipeg at that point. I hadn't lived in Winnipeg for almost thirteen years, so I came back with different eyes.

But I think Winnipeg found me again at the right time. I needed some quiet focus at my own tempo, and in a space where I could move freely without being too encumbered. The work I've been making here feels honest and bold, open to conversation, and a little bit out of step. That excites me a lot.

The community in Winnipeg is so caring, dedicated and resilient, so I don't have a desire to go elsewhere for now. There's too much to explore with my work in this current place.

I think it's important to have space—physically, mentally—while still having the ability to travel and go see work. The more I work in my own practice, the more I understand my need for breath—to give myself that time to think.

8. Do you think your practice would look different if you were based in another city?

Well, I've now been in three very different cities, so I know that my work changes in some ways as it responds to that context.

In Vancouver, I was in a small, shared basement studio without any windows, and I started really developing my work for the six years in that space after my undergraduate degree. That studio was a bit of a black hole for us—it felt like time would warp in weird ways, because there was no light, no information from outside. But we made our own strange open ecosystem there.

There's a lot of great, smart painting in Vancouver, so I found good grounding with the works of artists that were thinking of materiality—especially at that time—and surface and gesture. It was a nice contrast to Vancouver's longtime recognition as a photo-conceptual hub.

So, I think the city's dialogue helped shape my earlier work in many ways, but it would be hard to contemplate how my practice would look if I went back. It's a different city now.

In Guelph, there was a unique isolation that was quite productive. You could still take advantage of its proximity to Toronto, and take in a lot of good work. It was a small program; I had the privilege of having two wonderful cohorts in my time there. Many of them are still my closest friends—to share ideas, talk about painting, and debate and critique. My painting language grew more open, more vulnerable and vaster there.

But this was the result of the relationships I built, not the city itself. I did find a deep personal respect for smaller cities again when I was in Guelph—and for that pace. There’s a symbiosis with the way that I work in the studio, which often extends late at night into the early hours of the morning. Everything just feels more subtle at that time.

Q: The atmosphere of your studio seems important to your work—do you have any particular rituals around it, like playing music or keeping things quiet?

Yes, I always need some noise.

It depends on the stage of the painting I'm at—I have to be careful with what music plays at what moment, because it can have an influence, especially when I'm dealing with colour. So, in those initial stages, I tend to choose pretty factual podcasts because I can ignore them a little. They fade away and become that din of conversation in the background. When I'm in a small, gestural phase, then I can have music because the tempo can match that bodily movement.

9. What would you like to accomplish in the next few years?

That's a big question. I like to keep my focus on the moment and on the work I'm doing on a day-to-day basis. I have a lot of space to be in those moments here. I've felt quite loose so I can think of scale differently, I can think of shape and colour and the surface differently.

I am excited to keep playing with scale in the coming years—both large and very intimate. I think that desire has been coming out of my experience with this city, and with the space I currently have.

There's freedom in the unknown right now. Each day is just tethered to the two others that surround it, so it's bit by bit.

10. If there's one thing you hope people take away from your work, what would it be?

That painting really lives with us in the world.

It is rooted in the imperfect materiality of our bodies, of our experience—even when we can't explain how and why. Ambiguity is such a powerful and necessary part of painting.