THE INTERVIEW

Brody McQueen

1. Could you share a bit about your background and what led you to start your art practice?

I grew up pretty far outside the traditional art world. My mom's a teacher and my dad's a mechanic. So I didn’t have any connection to the art scene or knowledge of the art world, and it took me a very long time to know that what I was doing counted as art. I started out working in digital manipulation. I did a lot of altering reality in that way, but there was never a really solid concept through all of that.

It was more of a passion for me, something I found cool, so I kept creating. I was doing it for years and years and years—I think I started doing that when I was about twelve, and it was my main practice until I was about seventeen. I never saw it as art until my art teacher at my high school encouraged me to take a class with her.

In grade twelve, I took my first ever art class, and I had the pleasure to have it with Stacey Abramson at Maples Collegiate. She really opened my mind to the different forms of art because, again, I never saw that what I was doing was art; it wasn't drawing, and it wasn't painting. So I had a very narrow view when it came to my own art. I am so blessed to have taken an art class with her, and I think she shaped me into much of the artist I am today. Without her, my life would look very different.

After I graduated high school, I went into business at the University of Winnipeg, which lasted a year. It should have lasted a week—but it did last a year. After the first week, I knew that it wasn't really for me. I wasn’t particularly challenged by my classes, and I did well, but I figured, if I was going to do this for the rest of my life, I should do something I enjoy. So, in March of 2022, I applied to the School of Art.

I've been there for the past four years, and I really love it there. I'm currently finishing up the honours thesis part of my bachelors degree; then, next year, I plan to go and do my master's. I'm actually looking at schools right now.

2. What themes does your work explore?

My work often touches on themes of heritage, sexuality, community, the structures that shape public feeling, and, more broadly, memory. I'm interested in where we come from, where we are going, and who we inherit ourselves from.

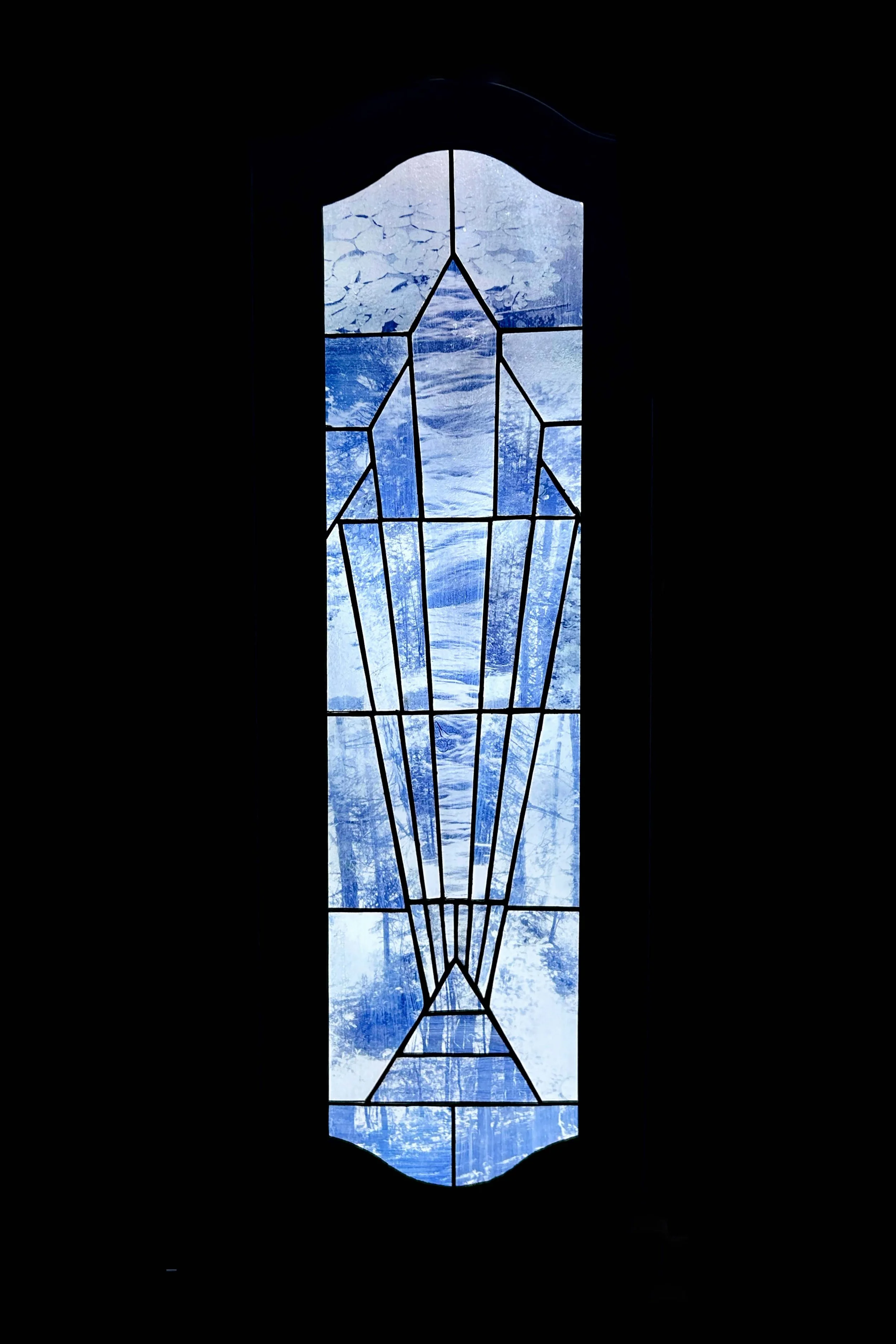

Currently, I am working on my honours thesis project, and I am focusing on queerness and the many facets within that experience. I am using photography, stained glass, and printmaking to investigate queer sanctuary; how those spaces are formed and what constitutes a queer place of worship.

3. How has your work evolved over the years and what has influenced those changes?

Well, it all started off with my digital manipulation work. I have kept all my early work up on my instagram, so you can still find it. I am not ashamed of my early work—it is a nice reminder of how far I have come. So yeah, I started off doing that, and it was great. I still use those skills every single day. I use those editing skills at my job, in my current practice, and even just in documentation photos of my non-digital work.

Over time, I think I felt a little bit suffocated by it—just because I never went into it with a concept, and when I had something I wanted to say with my art, I found myself gravitating to other means of communicating that. I started asking myself, ‘Why does this have to be a photo?’ And that was partially influenced by my art teacher. I love her so much. I wish I had taken more classes with her. She really got me to think outside of the box and start asking, ‘Is this the best medium to express what you're thinking?’ And I think that's where the shift kind of happened.

Because now, whenever I make something, I usually let the concept define the form it takes.

Before I make anything, I always ask myself if there is a way I can tie in the physical form to my concept. So, for example, I created a work called Ford Focus (2009) (2025) in which I used rust to print a photograph onto the hood of my car. I could have printed the photo digitally and slapped it on the car, or I could have used my Photoshop skills to edit the photo onto another photo of my car. but it was important to me to use rust for this, as it was symbolic to the work. I think considering process like that grounds an artwork in quite a wonderful way.

A lot of my work does relate back to photography, because I do see myself as a photo-based artist. But my consideration of the role the photo is playing and the form it takes is what I think makes my work stand out a little bit more. So I try to be as thoughtful as I can about the things that I make, and the role that the process plays in that.

4. What is the biggest source of inspiration for your work?

I’ve realized, after having to name my influences in various assignments, that I don’t really point to a specific artist or movement as my main inspiration. What I find myself constantly returning to is photographic history itself. I often look to historical processes and the long lineage of image making for inspiration.

So, yeah, I usually look to history for inspiration, but I am most excited about something when I can take a historical process and push it somewhere new. Right now, for example, I am currently working on some albumen prints for an upcoming show. It’s a nineteenth century process that I learned a while ago, and I have adapted it to fit the conceptual needs of the piece. Some photographic purists may see this as sacrilegious, but I never have more fun than when I am experimenting and bending the rules.

5. What is the most challenging stage of the creative process for you and why?

The experimentation phase—it's the most challenging, but it's also my favourite.

So much of what I do isn't written down in a book. I sometimes wish I could look in a book and have it tell me exactly what I am doing wrong, but that sadly just isn’t a reality for me.

Like with the albumen prints I mentioned, I had to do seventy test prints just to get an okay result because, in classic me fashion, I didn’t write down my steps the first time I tried the process successfully.

So I needed to workshop—try things—seventy times to get them back to where I wanted them to be. It was really, really rough in terms of deadlines, but we got there in the end. So, yeah—that is definitely my favourite and most exciting stage in the creative process.

Q: Is that why you lean towards working with scientists in your work—for that experimentation phase?

Yeah, I think so. I really like working with things that are new to me.

The historical research, things outside my field, working with other professionals—it just lends itself really, really well to the experimentation phase that I really, really like. And just a pursuit of, I guess, knowledge—because we are all lifelong learners, and that is something that keeps me excited about what I am working on.

6. What is the project you're most proud of to date and why?

I think it would have to be my blood-based albumen prints because that process didn't exist before I did it—to my knowledge, anyway. I'm sure that someone in the long history of photography has thought to try it—maybe some crazy Victorian-era scientist trying things out—but yeah, it was quite difficult to do.

I chose to alter that process because, in 1992, a policy was instituted that introduced a lifetime ban on blood donation for gay men. This policy was later amended to prohibit men who have sex with men from donating blood for five years after being sexually active. While these measures were initially implemented to protect patient safety following the Canadian blood system crisis of the 1980s, they ultimately perpetuated the harmful stigma that the blood of gay men was somehow less safe due to their sexual orientation.

This policy remained in place until 2022, when it was finally rescinded, accompanied by an official apology from the executive officer of Canadian Blood Services. I was particularly taken aback by the recency of this policy, and it got me thinking about the other holdovers and inequities queer people suffer in the healthcare system. That work has actually informed a lot of my recent inquiries in my practice, and I really think I will continue working in that way.

I think it's some of my strongest work conceptually, linking concept and process. I have been lucky enough to have exhibited that work quite a few times, and I have gotten a really good reception for being quite a visceral work. I see myself continuing this avenue of exploration during my masters degree in the coming years.

7. Do you see yourself staying in Winnipeg long term, or are there other cities that inspire you to work there?

I would love to visit somewhere else! I haven’t had the opportunity to see too many places in my life and I would really love to start exploring the world!

I do like Winnipeg, and I do see Winnipeg as a kind of home base—not because I have a huge family or anything like that; I actually have a very teeny tiny little family.

But, it's a lovely city, and I really have a strong connection to the art scene here. Especially working in a gallery—that has allowed me to interact with a lot of very interesting and kind people.

So I would probably use Winnipeg as a home base, but I would love to see the world and exhibit all over the world. It would be wonderful.

8. Do you think your practice would look different if you were based in another city?

I think so, yeah. Thinking about the queer side of my work, Winnipeg isn't the most intolerant city in the world—it's not horrible. So if I lived somewhere where that was punished, I think that aspect of my work would need to be a bit more hidden.

I try to stay clear from overt depictions of sex and some other things that you would more commonly see with queer art and stuff like that. I do think that being queer is so much more than just sex; obviously, it's a part of it—but a lot of it is also just being a person and being in love, just like everybody else. So I do tend to have queer undertones to a lot of my work, without explicitly saying it.

So, yeah, I think it would need to be even more hidden if I lived in a city that wasn't so welcoming. I’m lucky enough to have never met pushback with any of my work as it relates to queerness or anything like that, so I'm very fortunate in that way—and I thank Winnipeg for that.

9. What would you like to accomplish in the next few years?

Well, I would like to do my master's, and I do have an end goal of teaching at a university level. I'd love to teach photography—or anything like that—photosculpture, the history of photography, regular film photography; anything photo-based would be lovely.

I'd love to keep exhibiting locally, but also I'd like to exhibit in places other than Canada. I'm very fortunate this year—coming up in February, I'm exhibiting in Calgary, which is quite lovely, and it will be my first time exhibiting out of province.

10. If there's one thing you hope people take away from your work, what would it be?

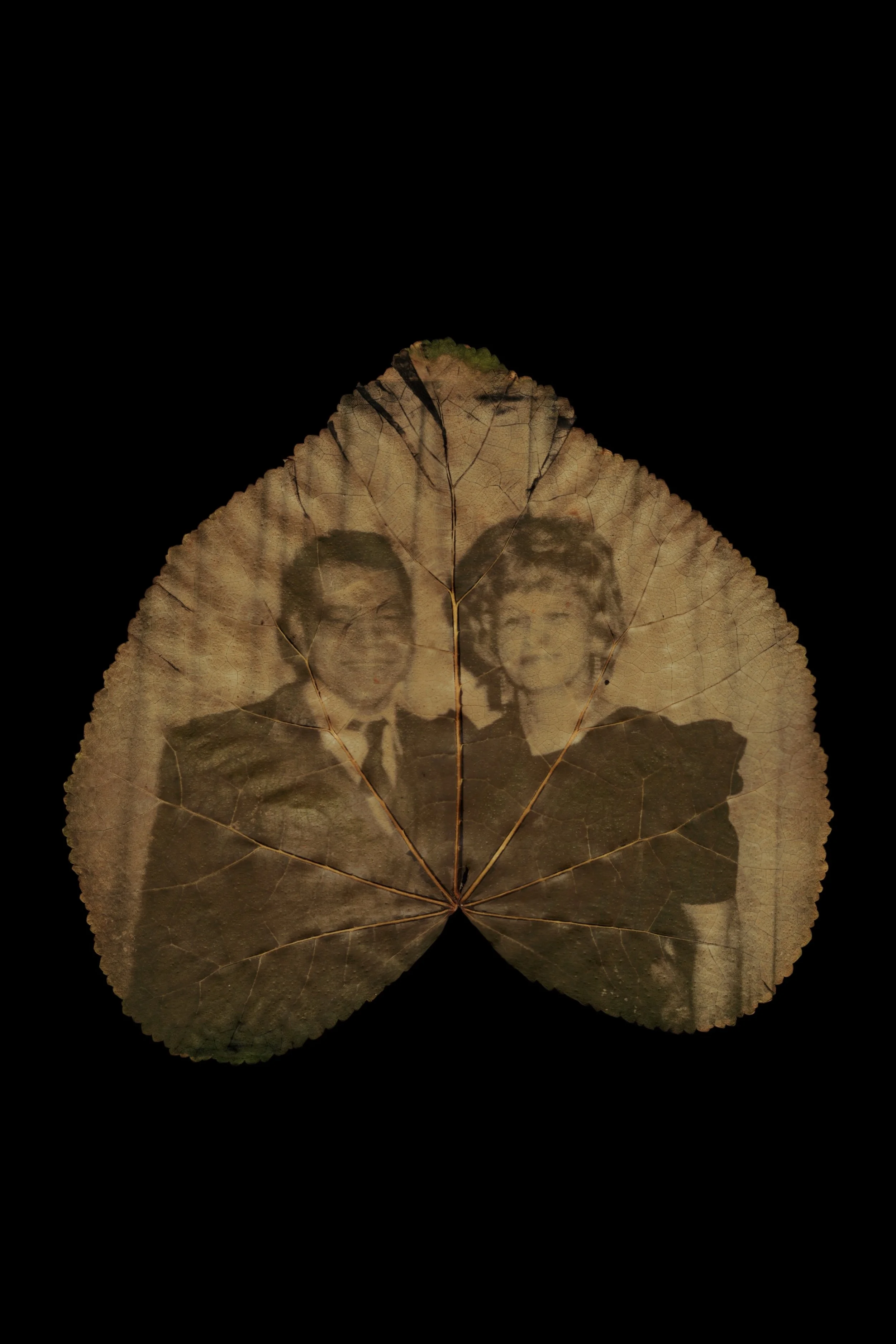

I hope people come away with an understanding that images, and the lives they hold, are not fixed. They can shift, fade, rust, stain, and change, just like memory, identity, and the queer sanctuaries I’m currently thinking about in my work. I’ve realized recently just how much of my practice is rooted in processes that evolve over time, like my rust printing, chlorophyll prints, and blood-based albumen.

By working with materials that degrade or evolve, I want viewers to feel how fragile an image can be, and how much responsibility is involved in witnessing something that might not stay the same. That act of looking—of returning, noticing, paying attention—becomes a form of care.